GET out and start walking. This is the advice continually given to sufferers from all manner of ills, mental and physical and everything in between.

And by and large, lacing up the trainers and putting one foot in front of the other does seem to be part of the answer. Or at least an excellent way of making the world begin to seem a better place.

Raynor Winn and her terminally ill husband, Moth, would certainly attest to that.

Although they did rather take the idea to extremes when they stuffed minimal gear into rucksacks last used in their long ago backpacking days and set out to walk the entire 630 miles of the ruggedly forbidding South West Coast Path.

They no longer had credit with the bank, no income, not much more than their clothes and a few bare necessities. They had already lost a costly three-year legal fight against the machinations of the financial system and a lifelong friend who turned against them.

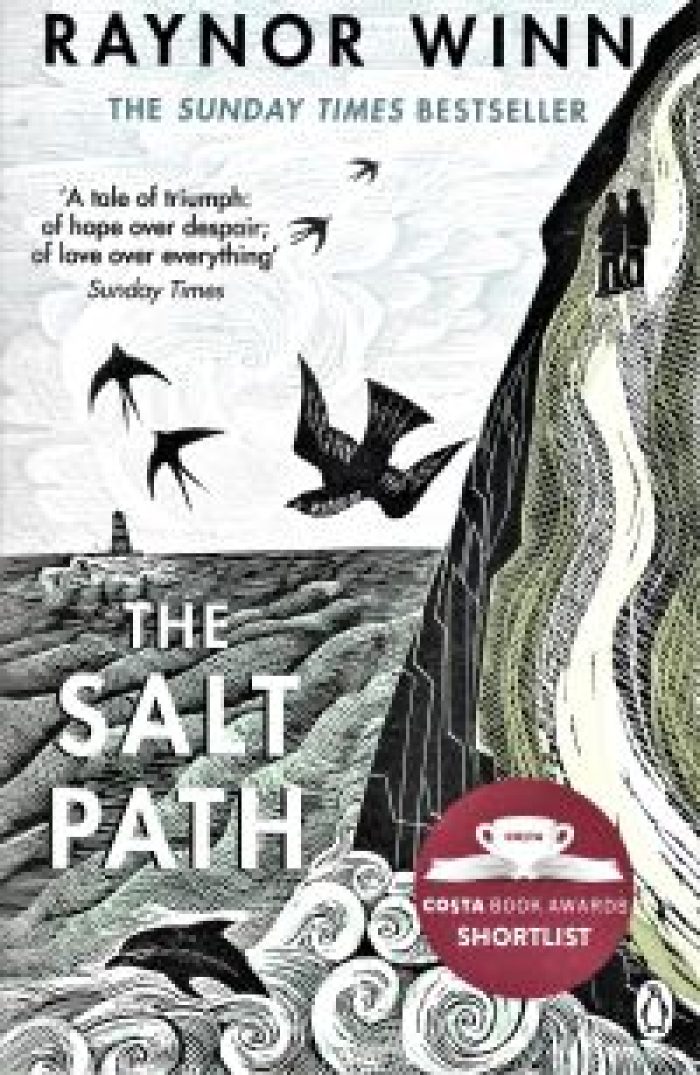

What followed from that is told by Raynor Winn in The Salt Path (Penguin), one of the most moving and beautifully written books in many a long day. A wondrous tug-at-heartstrings epic to inspire all who feel the odds are stacked against them.

There was acceptance rather than bitterness when Moth, suffering from a degenerative disease, is told he has mere months to live. Tolerance rather than a pursuit of revenge and retribution when, a few days later, their family home was taken from them. All goods and possessions seized by bailiffs.

When the doctors sentenced Moth to a greatly shortened life with increasing pain, Wynn as good as gave them the finger.

“Let’s walk,” was her response.

And so they did, the inseparable love of her life as ever by her side. After all, what was a 630-mile trek along some of the most rugged and exposed terrain England has to offer compared with the alternative?

There was nothing left to lose. Even to pitch a tent in a campsite would be beyond their budget of £48 a week in tax credits.

But they did it. Incredibly, these two mid-lifers survived all that this supremely challenging trek could throw at them. Walking (at times barely able to drag one bruised and bloodied foot on to the next step) became their salvation.

Leaky sleeping bags are their nightly beds. Sustenance is more snack than feast.

Sometimes nothing more than a chocolate bar has to suffice to provide the energy to take one painful step after another in the face of all that the weather gods can hurl against them.

There is occasional friendly help and support. Much surprise and admiration, even awe.

But overall there is scant understanding or sympathy on the few occasions that they reveal their circumstances. They learn there is little empathy for homelessness, regardless of the reason.

It is a story no one wants to hear – too harsh, too extreme, too unbelievable for middle England to want to have to think about. So they stop telling it when questioned.

Their inevitable scruffy, unkempt and often unwashed appearance attracts rejection, even aggression. Wild camping is not encouraged but they cannot afford even the cost of campground pitch for their tattered tent.

Such a synopsis hints at a tale laden with gloom, doom and downright misery. Far from it; quite the reverse. Wynn tells their story almost without complaint.

There’s none of the wailing and whining that is so often heard from those who suffer far less than is heaped upon her and the patient Moth, her deeply loved husband of thirty-two years.

These are two indomitable spirits, finding joy and delight where others would become gloom-laden and depressed. They revel in the great outdoors, come rain or shine. Both have a keen eye for the natural world; it brings them joy throughout their journey; lifts spirits; blanks out the travails of their travels.

Fortunately, Wynn is also blessed with the skill to bring their experiences succinctly to life on the page. Not only with keen observations of the path and those they encounter along the ever-changing trail, but on life in general. Rarely bitter, always pertinent and often with wry humour.

Despite the odds, they completed their walk. Moth’s health steadily improved to the extent that he resumed his studies, gained a degree and joined the staff at the Eden project in an environment closest to his heart.

It is not a new book (first published by Michael Joseph in 2018, my paperback version by Penguin in 2019), but an enduring one. One that has rightly sold more than a million copies and been followed by two more. An inspiring work for everyone’s bookshelf.

And now for another emotional trek …

UNLIKE Raynor and Moth (above), the subject of this story had no hardships to leave behind when he set out to post a letter.

UNLIKE Raynor and Moth (above), the subject of this story had no hardships to leave behind when he set out to post a letter.

But his journey was none the less arduous.

Pensioner Harold Fry simply ignored the letter box he intended to use and kept walking, leaving his unwitting wife vacuuming their bedroom.

He was totally unprepared – no changes of clothes or gear to cope with variable weather, the wrong shoes for long hikes, no food or drink and his mobile phone left behind at home.

He did at least have a definite destination in mind. This was the far northeast of England, several hundred miles from his cosy suburban home on the Devon coast.

That was where the sender of the letter, Queenie Hennessy, an old flame and work colleague from many years ago, now lived. Or more precisely, where she was now close to death.

As her brief note informs him, she is dying from cancer.

The return address is a hospice in Berwick-upon-Tweed, proof if any is needed that her life is indeed ebbing away.

Harold last set eyes on her two decades ago when she suddenly left her job as bookkeeper at the brewery where he was a sales rep.

Her letter is a trigger that fires a starting pistol setting Harold, impulsively and compulsively, on a mission from one end of the country to the other. Unplanned, without maps, with little sense of direction other than to head ever northwards.

It is an exploit beautifully conceived and described by Rachel Joyce. Almost as if she has walked every inch of the way in Harold’s relentless footsteps. The landscape, the flora and fauna, the people and the incidents are acutely observed; needle sharp and not a word wasted.

She seamlessly assumes Harold’s persona; his continual bemusement at the wider world, his innocent willingness to engage with all and sundry, regardless of the rejections, barbs and insults that sadly are hurtful.

And every person he encounters is totally believable, finely drawn and living on the page.

Harold is fired by a false belief that his presence will somehow save Queenie’s life. Nothing else matters.

The agonies of his progress are relieved by thoughts of the few other landmarks in an uneventful life: his romance with wife Maureen, the birth and suicide of their only son, David, and how (and why) they have diverged yet remained stolidly together.

He ponders how they have become what they are today.

Meanwhile, back in the home she spends her life keeping meticulously spotless, Maureen finds Harold’s absence is also leading her into reflections on what might have been.

Her initial anger at his unannounced departure slowly softens. She even looks forward to his spasmodic reports of progress. Might she yet hope he reaches his goal, cheer him on, even understand what drives this man with whom she has no meaningful conversation for years and years?

Like Raynor and Moth above, there is an end (spoiler alert!) – and a beginning.

Walking really does work wonders for body and soul – and for those who like a really good read.