SUDDENLY I am delving into my memory bank, reliving how it was to take that nerve-racking walk from West to East across Berlin’s no-man’s-land of Checkpoint Charlie.

An instant recall sparked after inexplicably waiting two decades to open a book fully intended to be read when it made its spectacular debut in 2003.

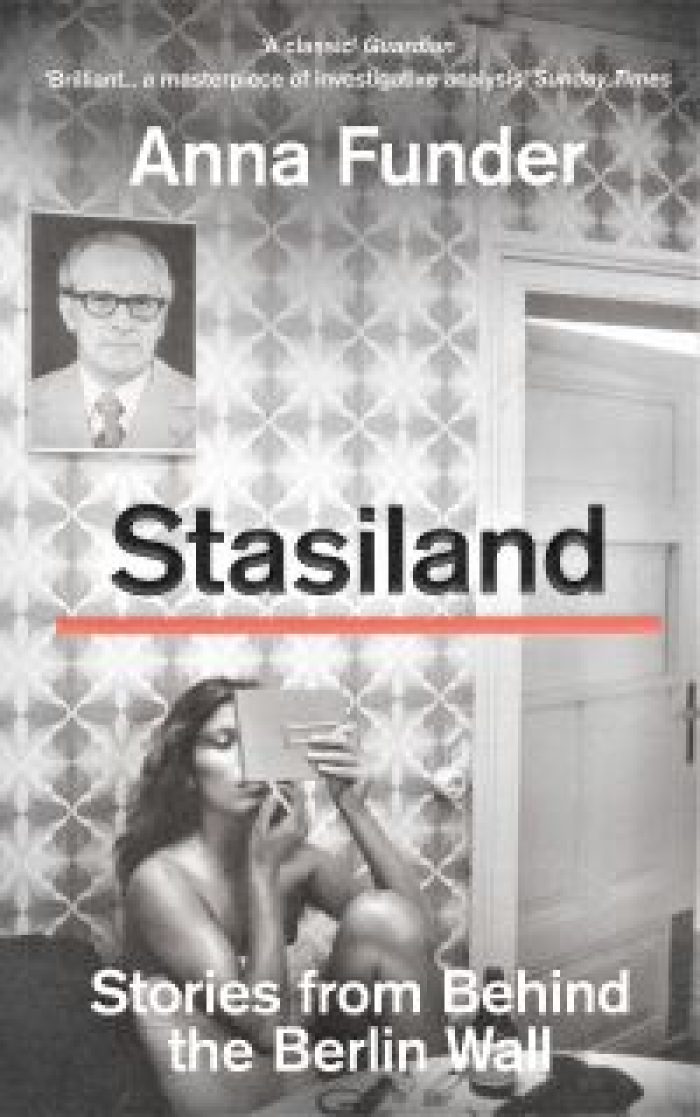

That’s how it was with me and Anna Funder’s Stasiland.

Launched to an avalanche of plaudits at the start of the century, it stayed on the best-seller list for close to two years.

But only recently has it made its way to my bedside pile, the result of a fortunate impulse buy at the local Waterstones.

And once opened, all other reading was put aside. So compelling, so many knife-edge moments. And so much to stir old memories.

Could there be anything more chilling than crossing that great divide? Anything more likely to arouse every nervy sense? Trying to appear relaxed and ho-hum while aware of unsmiling military to front and back.

The Wall was still there when Funder – a German fluent Australian – first spent time living and working in West Berlin in the 1980s. She wondered “long and hard about went on behind that Wall”.

But it was not until some time after the Wall came tumbling down in 1989 that she actually visited what had been the German Democratic Republic.

She did so by the more mundane way of taking a train to Leipzig. No anxious walk under the gaze of trigger happy border guards.

Yet what she discovered is no less unsettling.

She takes us into the secret world of the Stasi – the East German Ministry for State Security – which held its citizens in a cruel iron clasp.

No one was safe from its vigilance. Friend spied on friend; mistrust divided families. Every detail of everyone’s life was noted and documented. A massive collation of the minutiae of daily existence.

As Funder notes, if laid out the files kept by the Stasi would extend for 180 kilometres.

She visits the vastness of the former Stasi headquarters, transformed almost overnight into a museum of its reign of terror.

Everything from the horrific to the laughingly ludicrous; from the cells from which few returned to a glass case displaying empty jars.

These once contained smell samples, secretly gathered pieces of clothing that would be used by sniffer dogs to track down alleged lawbreakers.

This is but the starting point of Funder’s journey into the darkest corners of the Stasi. As a lowly staff member with a German TV station her job is to respond to viewers’ letters, many of which pose queries centred on life in the post-war years.

She makes it her mission to unravel the past on behalf of a handful of the letter writers, but particularly Miriam who, in her own words, “became officially an enemy of the state at sixteen”.

She and a schoolmate had made leaflets protesting against the demolition of Leipzig’s old University Church.

Parents of school friends dobbed them in to the Stasi and within a day Miriam was being stripped and forced under a bath of cold water before being dragged up by the hair. And again. And again. And again.

Miriam is a survivor. She marries a fellow Stasi victim. He disappears and Miriam falls once again into their clutches.

Her horrific story and those of other writers of Funder’s viewers’ letters are recent history. Very recent yet many remain hidden, still being discovered and needing to be discovered and told.

Shredded documents are being sorted and pasted back into readable form by “the puzzle women” whose task is to restore shredded documents to their original form.

Stasiland merely scratches the surface. But in an intensely moving and personal way. The sheer madness of what was happening even after the wall came down makes compelling reading.

Funder is a compassionate and sensitive recorder of what befell those whose stories she tells. And also of the people and daily life she encounters on her journey.

All so acutely observed.

There is humour among the sadness and pain, but never any excess; no need for tabloid journalism – the facts are painful enough.

They linger long after the final page and should never be forgotten. A brilliant investigation of recent history that is so readable and accessible.